On a cruise to the mid-Pacific to view the total solar eclipse of April 8, 2005, I sat at dinner one evening near Tomasz Mazur, a young mining engineer from Poland. I told him about my Copernicus project and said I would soon be visiting his country. Without hesitation, he asked for the dates of my trip, offering to take time off work to serve as my translator and guide. Copernicus was his hero, Tom volunteered, and it would be his pleasure to accompany me to the cities where the astronomer had lived.

Tom fulfilled his promise that summer, and again two years later, when I returned for a second round of research. We enjoyed our finest hour in Krakow, being treated to a rare, private glimpse of Copernicus's hand-written manuscript for De revolutionibus. The curator held the volume in gloved hands and opened it to several interesting pages -- the iconic diagram of the Sun-centered cosmos, the author's ink-smudged fingerprint in a margin. She told Tom (in Polish) how unusual it was for the priceless document to come out of its temperature- and humidity-controlled safe. As we left the building, Tom compared the viewing to the eclipse we'd seen together: difficult to achieve, over too soon, but stunning and unforgettable in its impact.

Staying in touch with Tom by e-mail, I knew he wanted to visit the States, most of all to see a Shuttle launch. Last February, thanks to another friend's good luck in winning a lottery for launch-watching privileges in the Kennedy Space Center's Rocket Garden, I invited Tom to Florida. Finally, I thought, I might return one of his countless favors.

The launch experience proved as addictive as eclipses for Tom. He returned to Cape Canaveral with his brother earlier this month, to witness Atlantis's last lift-off. Since I couldn't join him this time, he sent me a report:

We came to Miami 7th of July in the afternoon, drove several hours north to our booked hostel in Kissimmee, and were quite tired and sleepy at 11 p.m. when we finally arrived. I was especially afraid about my brother who was driving whole time after long, tiring flight from Europe (with overnight in Madrid airport), so the news about poor weather prospects and 70 percent chance for postponing the launch didn't make me very happy.

At 3 a.m. we learned that fueling was underway, and we left for Jetty Park, our chosen place of observation. We got there at 4 a.m. and found really great spot on small mound. We put our tripods there immediately and pointed our cameras on the small white point on the horizon (about 16 miles away), which appeared in the viewfinders as beautifully lighted with powerful beams. In that chilly night it was the only moment when the Shuttle was clearly visible and we could take pictures of it on the launch pad.

After sunrise haze rose from the lakes and canals, and one could see no more than a gloomy irregular shape in the distance. As the hours passed, the weather got better, mocking all forecasts for heavy rain. About one hour before the launch we knew we were on the way to see the take-off. Now only technical problems could stop it. Everything was going smooth even in that area, and for a few minutes my heartbeat quickened and this special kind of excitement I always have before the eclipse arose in me. I started to believe that we will be presented with that wonderful experience against all odds and grim foresights, but when I was gluing my eye to the camera and placing sweaty hands on the remote release at T minus 31 seconds, we heard on the NASA radio that some failure occurred. All the people around us stopped their breath and froze. We knew only a few minutes remained to solve the problem before the start window will close. Voices in the radio started quick and tense information exchange, and even though I couldn't understand everything, I felt tremendous tension and nervousness in those short sentences. No, not at the very end! I thought to myself. And then with great peak of hope I caught a sense of relief in the next communications, and, with cheerful applause of all people gathered around, the countdown resumed and we saw the flames of main engines and solid rocket boosters a few seconds later.

The column of plume rose to the sky and pierced the first layer of clouds. A glimpse of fire appeared one or two times more in the scatterings. The sound reached us long after the last visual contact with the climbing spaceship.

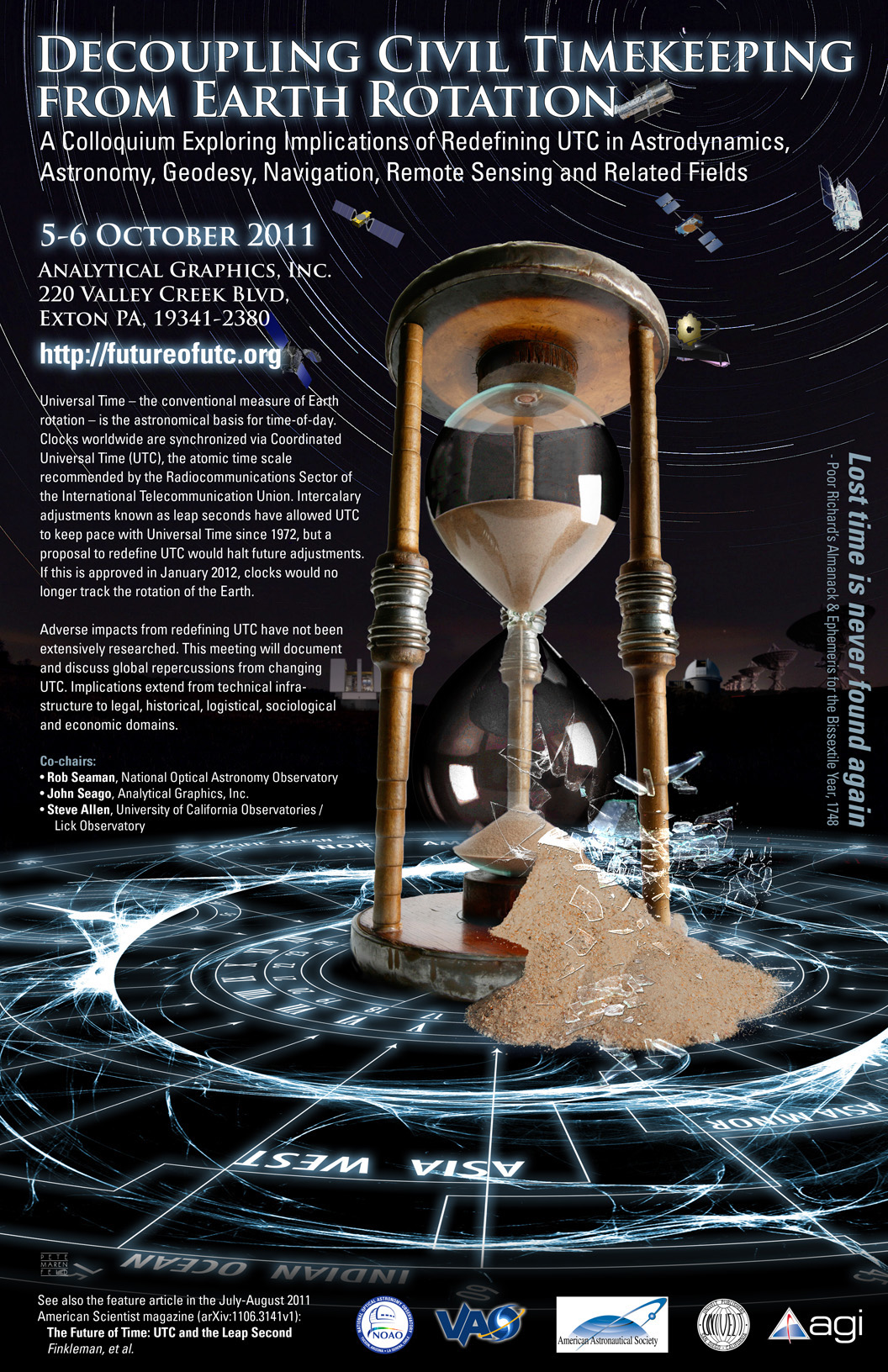

That was the end. We abandoned the Moon and our aspirations for Mars, as well as other ambitious goals in space conquest. Now we canceled the most advanced and versatile spacecraft. Next years will bring us slow degradation and finally sad end of Hubble telescope and ISS unavoidable retirement. No one really believes in loud but empty words about return to Moon and building the base there.

To finish this letter less grimly I want to tell you that in the days after the launch we had great time exploring the main nerve of America and American Dream, as Hunter S. Thompson described it, visiting all theme parks around: SeaWorld, Universal Studios and Disney. We also toured Key West, but the thing I will remember the most (excluding the launch itself, of course) from that short sequel to my holidays will be the night before my birthday spent jogging on the beach with full Moon above and silent ocean silvered by its light below.